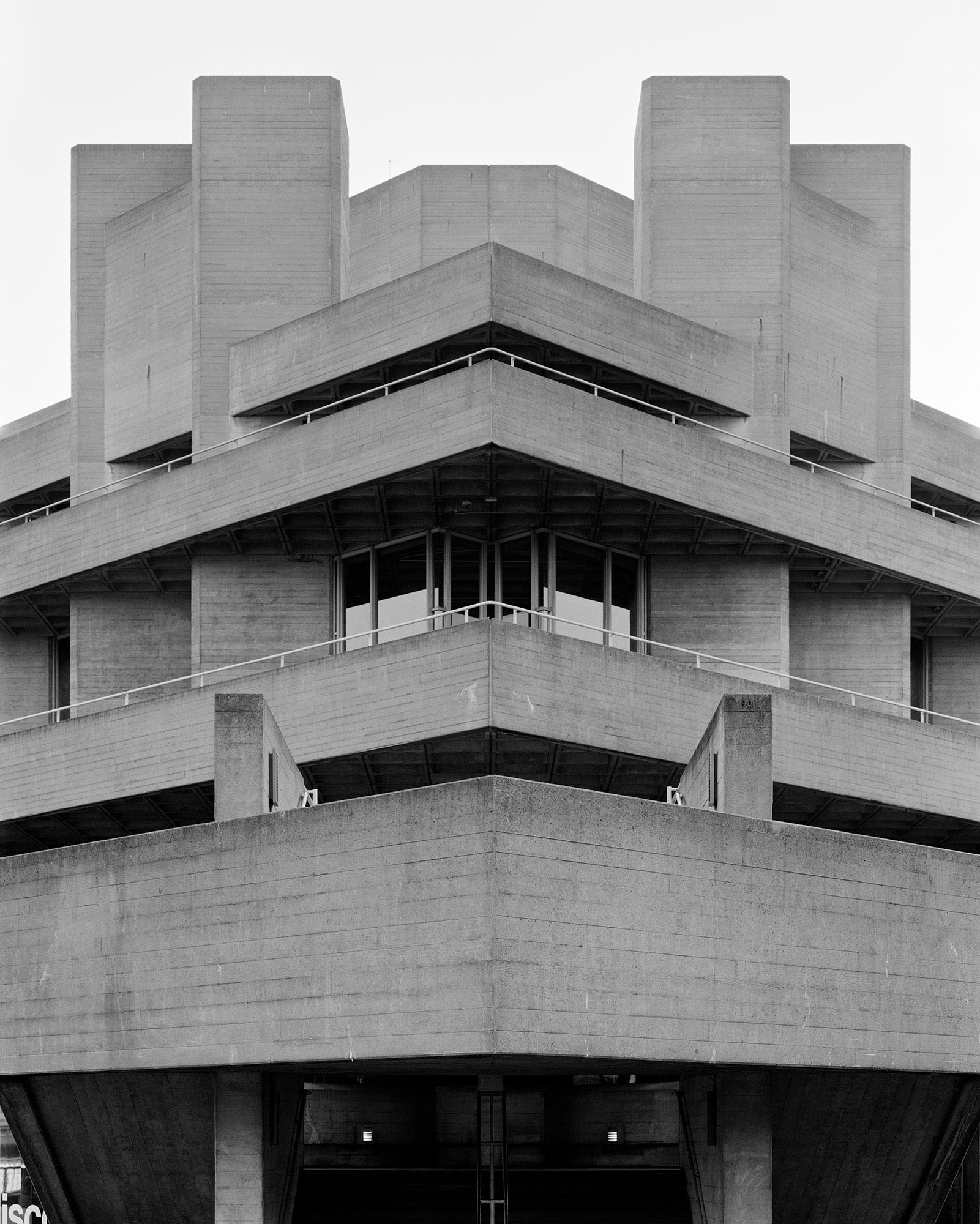

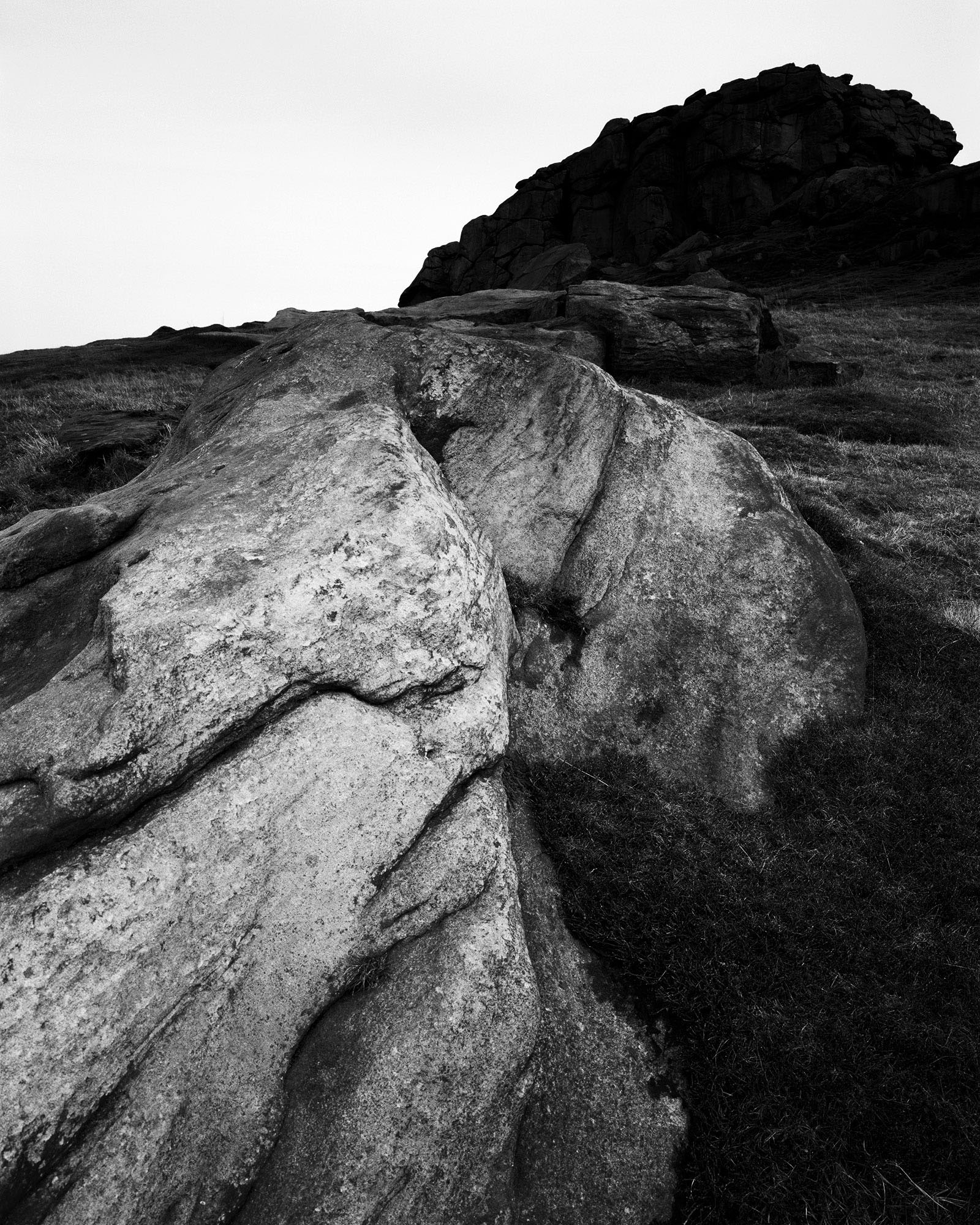

GEOMETRY + GEOLOGY

Geometry + Geology is an exploration of the formal and expressive affinities between Brutalist architecture and rock formations in northern England. The Brutalism I’m concerned with is concrete architecture in London from the 1960s and 70s. The name derives in part from Le Corbusier’s use of the term ‘béton brut’ (raw concrete) to describe the unadorned, and frequently rough-sawn timber-shuttered concrete structures of his later works. By ‘formal’, I mean shape, line, massing, surface texture, colour, etc. By ‘expressive’, I mean our capacity to recognise objects as conveying a mood or atmosphere which engages with our emotions. (A theory of expression is important to my work, but a little convoluted to get into here.)

“The point of philosophy is to start with something so simple as not to seem worth stating, and to end with something so paradoxical that no one will believe it.” Bertrand Russell

SIMPLE OBSERVATION #1: Frequently, architecture looks like other things.

1. Architecture has often been designed explicitly to look like other things; sometimes elegantly, sometimes comically. For example, statues embedded in Egyptian columns, acanthus leaf mouldings on Corinthian capitals, Gothic rose windows, the oil refinery imagery in the Lloyd’s Building, the eagle form of the TWA Terminal at JFK airport in New York, and the Longaberger Basket Company HQ in Newark, Ohio.

2. Sometimes resemblances are seen which may not have been intended. Often, these are comic, such as the ‘Gherkin’, ‘Cheesegrater’, or ‘Walkie-Talkie’

3. To my knowledge, few architects or critics have made any sustained comparison between Brutalism and landscape. The usual comparisons are with ships and castles. An exception is Denys Lasdun, who conceives the articulation of circulation routes in some of his buildings as akin to geological ‘strata’. Jonathan Meades also makes a comparison with waterfalls in his film ‘Brutalism, Bunkers, & Bloody-mindedness’ (2014).

SIMPLE OBSERVATION #2 People hate Brutalism

There’s probably a sizable majority of the population who regard Brutalist architecture with a mixture of incomprehension and contempt. The phrase ‘concrete monstrosity’ is a familiar refrain in the popular press.

Sir Simon Jenkins wrote in the Guardian: ‘Two long cliffs of grey, stained concrete enclose mean staircases, narrow decks and unusable balconies, a prison without a roof endured by 600 people for half a century. The east London Pevsner guide calls Robin Hood Gardens "rough and tough ... ill-planned to the point of inhumane". Not one current resident to my knowledge has stepped forward in its defence. Had the estate not been designed by two gurus, Peter and Alison Smithson, no one would be shedding a tear. ...The Smithsons were ideologues of the “street in the sky”, the vertical village, the Clockwork Orange tunnel, the urinal stairwell and shuttered concrete. Their ethos was so influential that hardly a British town is without some Smithsonian pastiche, like London’s Hayward Gallery. They were an ugly blind alley in urban design, rejecting the street life and humanism espoused by writers such as Jane Jacobs in favour of a brutal Corbusian totalitarianism.’

The main point to notice is the ease with which Jenkins associates the materials from which the building is made with problems he identifies with its spatial design and use, such that any other building of similar style is condemned from the outset.

SIMPLE OBSERVATION #3: People love the rock formations of northern England.

They are National Parks; protected landscapes; scenes that feature on popular postcards, etc. All year round the hills are a place of leisurely pilgrimage for picnickers, walkers, and all manner of outdoor sports enthusiasts. Countless pictures celebrate the landscape’s verdancy and its ruggedness. The bucolic and the sublime coexist happily in the minds of most, it would seem.

PARADOXICAL OBSERVATION: Brutalism is the architectural image of the rock formations of northern England.

The dark and sinister is visible in the celebrated and familiar, and vice versa—a special instance of the Freudian uncanny.

COMPARISONS

The similarities I aim to depict are the sense of sublime scale and monolithic bleakness. The rough, weather-stained face of the shuttered concrete resembles the irregularities found in the erosion-scarred terrain of mountain rock. The darkness of the material in wet and grey weather matches that of the frequently dour conditions of the mountains. The shadowy nooks and crevices inspire trepidation and invite exploration. In The Seven Lamps of Architecture, Ruskin writes of the significance of ‘power’ (or the sublime) in architecture, citing the epic, uninterrupted wall, the ‘precipice’, as the archetypal expression of abstract power. The effect of severe, unyielding magnitude also carries with it a sense of melancholy in its solitude. The Brutalist buildings photographed exemplify this sense of imperviousness: solitary, stark, with intersecting planes conveying a sense of geological force and weight. The geometric compositions add to a sense of abstraction. There are no obvious symbolic forms introduced by the architects. The geometry is strong, but irregular. The buildings, considered as wholes, do not have lines of symmetry; again, suggesting a comparison with mountain rock.

The series is photographed on Ilford HP5 & FP4 5x4 inches sheet film. Limited edition prints are available from my shop.